Well – the eagle has finally landed! Or perhaps I should say that it has finally taken off, as I launch this new website of Chris Ellis Art, showcasing some of my paintings and sketches and providing a new home for my blog Crammed with Heaven. I hope you like the new header image, a detail from one of my paintings of a golden eagle, highlighting both my delight in painting birds and other animals and hinting at the focus of my blog: the connections between art and spirituality.

The eagle has long been a symbol across human cultures, often using the eagle as a symbol of power. After all, it is at the top of the avian pecking order – so think of the imperial eagle and its potency in heraldic displays. But the eagle has also been admired for its majestic flight and it is this which has made it an important symbol in Christian art.

Many historic churches will have lecterns where the Bible rests on the wings of an eagle. The Word of God comes from above and is winged to all corners of the earth in mission and proclamation. The eagle declares that this is not just any book, but comes from God and lifts us up so that we, like the promise of Isaiah 40.31, might soar like eagles.

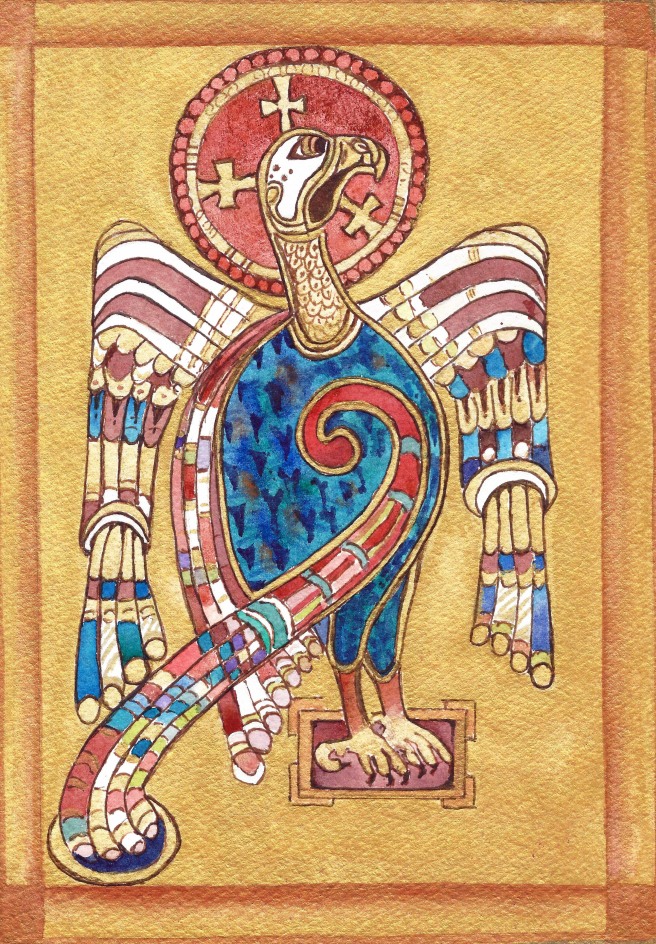

The eagle had also long been the symbol of St John the Evangelist and here is my watercolour copy of an illustration of this eagle symbol. It is from the Book of Kells, an illuminated manuscript book of the four Gospels. Regarded as one of the greatest treasures of Insular Art, the Book of Kells was probably created around 800 CE either on Iona or in one of the other monasteries which had been founded in Britain or Ireland by St Columba (521-597) and his missionary movement.

Connections have long been made between the symbolic living creatures in the visions of Ezekiel 1 and Revelation 4. The first writer to do so was probably St Irenaeus, bishop of Lyons in the second century CE, and he and later writers linked particular gospels to particular creatures in a variety of ways. But it seems to be St Augustine of Hippo and St Jerome the Bible translator, both writing around 400 CE, who first associated the eagle with St John Gospel.

The most common explanation for the symbolism, both if the lectern eagle and of the Fourth Gospel, is that the eagle was believed to be the only bird who can look or fly directly into the sun. Whether this is, or is not, ornithologically correct is beside the point. It is the symbolism which matters. Struggling to follow the soaring flight of this majestic bird will have left countless observers blinking blindly into dazzling sunlight.

At one level, John’s Gospel takes us to heights and possibilities beyond our earth-bound concerns, even though there is much of suffering and humility also to be found in it’s pages. The nuances of the Gospel’s presentation of glory’ are for another blog, another time! For now, we can celebrate the way it enables us to soar as well as go deep.

Symbolism is a fertile but tricky business and often won’t work in a reverse direction. We mustn’t imbue eagles with spiritual or anthropomorphic characteristics. This predator of the sky, this majestic hunter, is one of God’s creations – a creature of beauty and strength, of grace and elusiveness. Let us celebrate the bird, while also allowing it to nourish our imagination.